It is the early 1990s. All is dark, except for the car’s illuminated control panel and the swath of road directly in front of us. My dad drives. My mom and sisters sleep. I sit in the back seat, silently watching roadside reflectors flare, zip past, and disappear.

We are driving from our home in western Nebraska to the state capitol, Lincoln, and it feels as if we’ll never arrive. The sun set hours ago. The moon is a sliver. The world has disappeared, aside from that small swath.

I crane my neck and peek forward from time to time, hoping for a sight of buildings that never appear. We drive through open country. There is nothing around us.

I begin to lose hope. I begin to think this is purgatory. I will be cramped in this back seat forever.

“Look,” my dad says.

I lean forward. Beyond the swath of headlights, I can just see it on the horizon. A faint arc, glowing. The city’s lights, still distant. More suggestion than reality.

We continue on, and I train my gaze ahead. Little by little, the aura grows larger.

There is a story, perhaps apocryphal, about the playwright Tennessee Williams. In this story, Williams is near the end of his life. A friend comes to visit. As the friend walks through Williams’ office, he sees some paper in the typewriter and grows excited. Is this a new work?

And then the friend looks closer, and he sees that it isn’t something new at all. It is one of Williams’ famed plays. Perhaps The Night of the Iguana or Streetcar. The lines are overwritten and marked with red. The friend inquires of Williams, “What are you doing?”

Williams explains that he is rewriting the play. Even though it’s already been produced to great acclaim. Even though he’s already been praised endlessly for it. Still, he tinkers.

The friend has a simple question: “Why?”

Williams’ answer is just as straightforward: “It isn’t perfect yet.”

For the past couple of months, I’ve been busy with a rather strange bit of work. I have been rewriting my debut novel, Godfall. Fairly significantly rewriting it.

The strangeness lies in the fact that Godfall already has been published. It has received quite good reviews. It has won a couple of awards and been nominated for others, including making the Cabell Long List. It has sold foreign rights and come out in audio. And it has been scooped up for a TV show amid a Hollywood bidding war.

So, you might ask, what am I doing tinkering with it? Why not move on to something new, like the forthcoming sequel?

The short and practical answer is that Godfall is moving to a new publisher in a new edition (more about this soon). I’m also working with a new editor.

That said, when I made this new deal, I was told that the book would be fine as it was. The editor had suggestions, but I didn’t have to change a word if I didn’t want to.

It was my choice.

Another story. My friend Robert Venditti, the great comics writer, once was at a comics convention and was talking to the late cartoonist Ed Piskor.

Ed was talking about his work, and he said that he drew one page every day. And so, every morning, Ed would wake up with a vision of a perfect page in his mind’s eye. And that would be his goal—to render that perfection into reality.

And, every day, he would fall short in one way or another. The page never came out perfect. It never lived up to the vision.

Yet, he ended every day with one more page drawn.

It is the late 1990s. I’m in high school. It’s winter, which means windy and goddamned cold. My family has a couple of horses, and though I am the only one who doesn’t ride them (and doesn’t much like them), I walk out to the pasture to tend to their welfare.

We aren’t able to run electricity this far from the house, so the horses’ stock tank isn’t heated. Which means in this zero-degree weather, the water in the tank freezes over. Which means the horses can’t drink.

This is why I’m carrying a maul with me. It’s a sort of cross between a sledgehammer and an axe.

The ice in the tank is about half a foot thick. I lift up the maul, swing it down. The ice chips, shards of it spraying back. Some of it slices my face. I bring the maul up and down dozens of times. Finally, the ice is broken. I scoop it out with a pitchfork. The horses come and drink. I deposit the maul back in the mower shed and go to my car and drive the ten miles to school.

The next day, I will do this again.

Godfall has lived a long life, as new as it is. I first wrote it in, I think, 2017. My literary agent at the time never read it. (Pro tip: Good way to know you should fire your agent.)

I found a great new agent who loved it, and I did two big rewrites of the book. Then the pandemic hit as we were shopping it, and in that early panic, publishers weren’t acquiring anything. Finally, I landed it at a small press.

Then my film/TV manager made magic happen, and it became a bit of a phenomenon, the little book that could.

And as the TV show moves ahead (more on that soon as well), we realized we needed to bring the book to a larger publisher. Thankfully, we found an amazing home for it with an editor who loves it.

And that was how I came to the choice. To revise, or not to revise.

When the editor asked me what I wanted to do, a big grin came across my face.

“Oh, I have been WAITING for someone to ask me that,” I said.

The thing is, no matter how well I write, it’s never perfect. And it’ll never be perfect. Any writing I ever produce will be flawed in one way or another. I’ll fail to explain something clearly. Or choose the wrong word. Or miss the implications of a plot point. Or, gasp, make a typo or two.

I always see the perfect thing in my mind’s eye. And I never reach it.

I don’t think of myself as any sort of genius who spits out the sublime. I am, more than anything, the kid with the maul over my shoulder, trudging out to the stock tank.

What I am is a worker. And while I can’t will myself to be a genius, I can will myself to put in effort. The key is focusing that effort in the right way.

This is something I call good-to-great. So, let’s dig into just what that is.

Good-to-Great

You know that feeling when you’ve written something, and you feel really good about it, and you’re ready to share it with the world?

What if, in that moment, you stopped yourself from that impulse? Instead, you took a little break from the work, then came back to it with fresh, critical eyes. You go page by page, line by line. You kick the tires on all of it. You put every word to the test. Is this as good as it can be?

The answer, more often than not, will be, “No. This could be better.”

And, then, you dig into the effort of pushing it to the next level. Fixing weaknesses. Building on strengths.

That is good-to-great.

Is this hard? Yes. Does it require you to put aside your ego and pride? Absolutely.

What’s most challenging about this for me is that, every time I write something, I learn from that experience. I’m a wiser writer for the effort. Which means, I hope, that I’m better than when I began. And if you track that logic, it means that, no matter what, I will always look back on what I’ve finished and see the flaws, the things I did poorly.

I am a better writer today than when I first wrote Godfall in 2017. Or when I rewrote it in 2019.

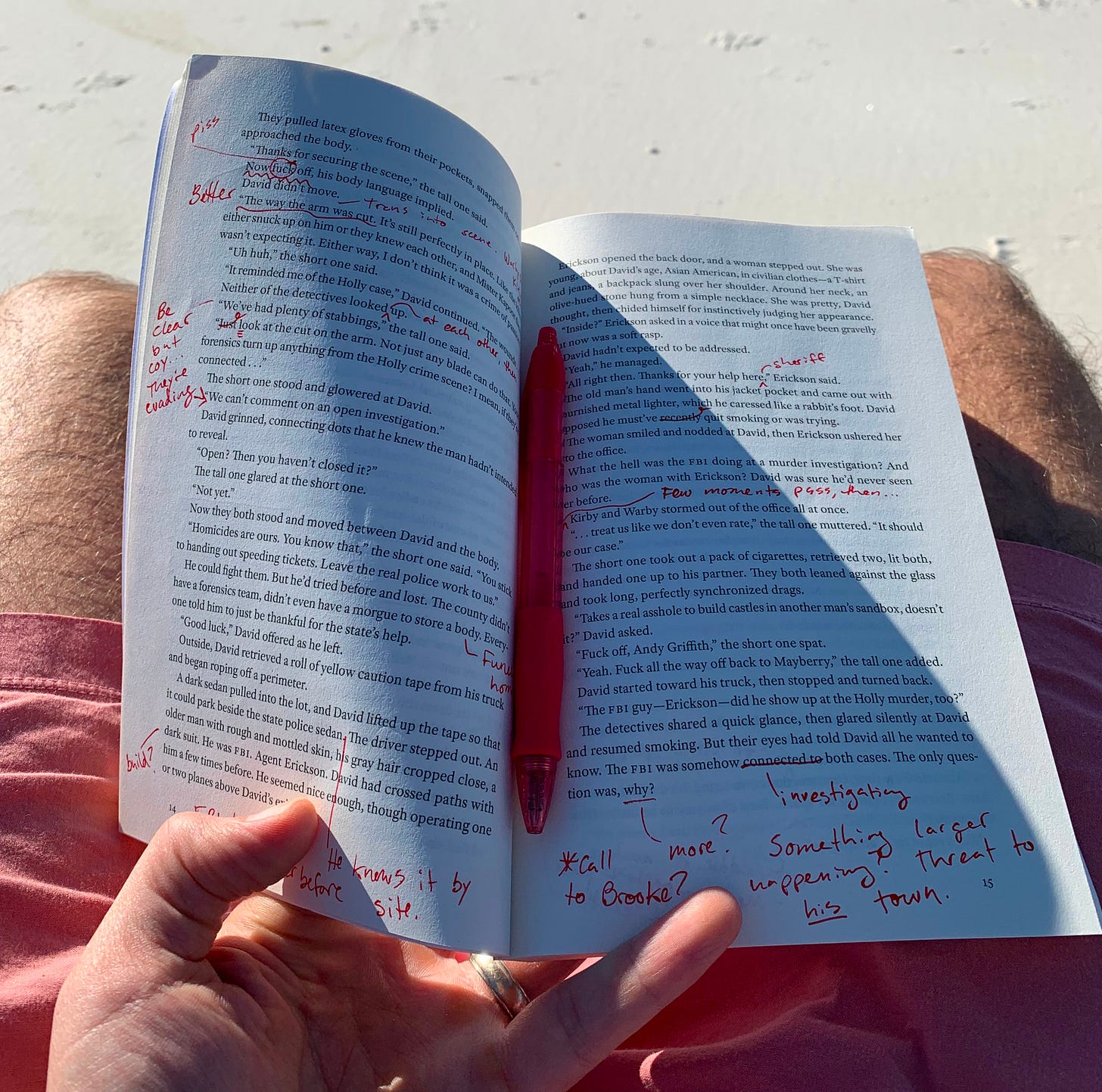

When my new editor sent me his notes for Godfall, I didn’t blanch, because they weren’t nearly as comprehensive as my own notes. I bled out a whole red pen.

The pages I marked up were filled with swaths of underlined text and a repeated notation: “D.B.” This means, simply, “Do Better.”

Is this new version of Godfall perfect? No. Is it better? Significantly. Is it great? Closer to it, anyway. Was it hard work? Of course. Do I regret the effort? Not one bit.

We are all finding our way through darkness. Ahead, the city glows, beckoning. A vision of arrival, of perfection.

Little by little, we progress toward it. The glow brightens, expands.

We will never reach it. Still, we push onward.

As always, thank you for reading. If you’d like to learn more about me and my writing, please visit vanjensen.com. You can like and comment on the post below! Till next time…

Excellent! I can't wait to read the new version. ( I also have high hopes for a hardcover copy. )

As challenging as our rural Nebraska upbringing was, it taught us at least one thing: how to work.